This is part of a serial experiment with and around Tanzil Shafique‘s ongoing writing project, A Thousand WetLands: Southern Thinking against the Gods of Coloniality.

Have you ever been inside a coal mine?

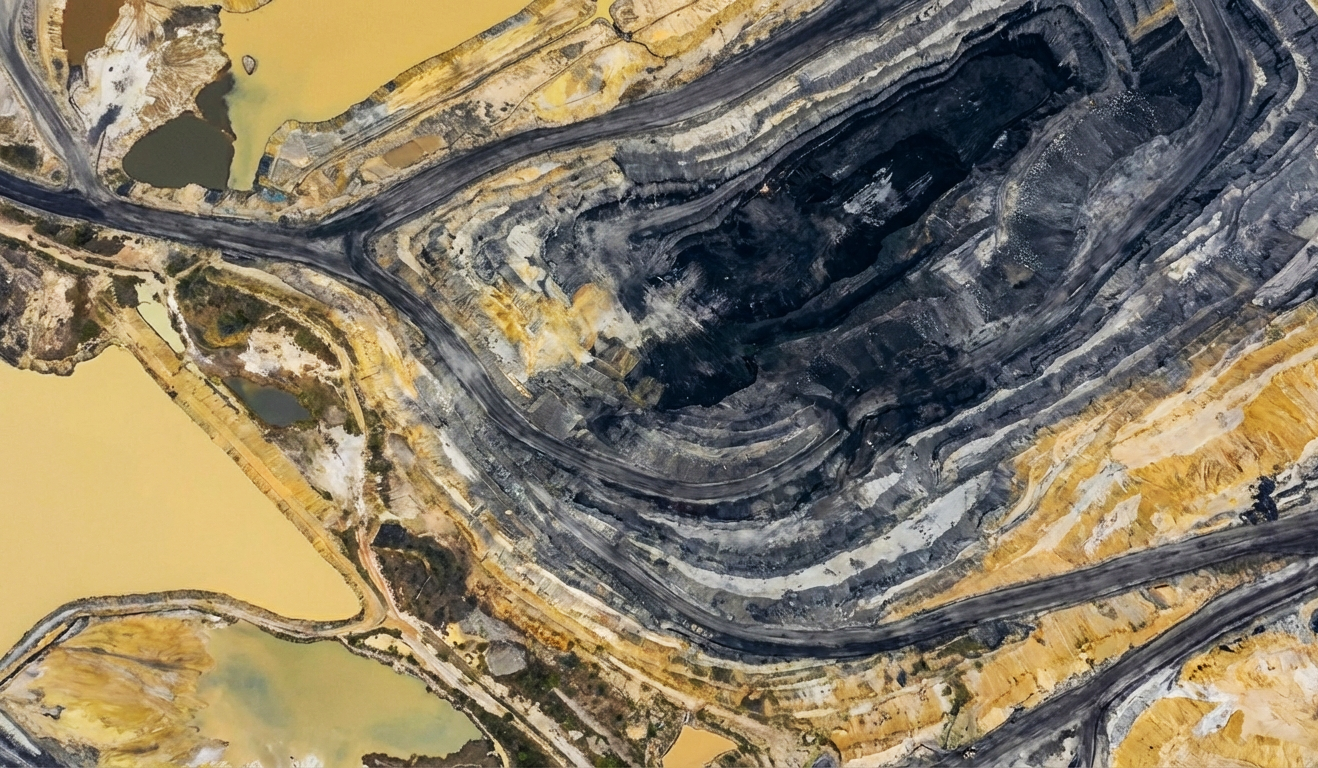

We were brought, on a field trip, to Gresford Colliery’s abandoned heart. I stood there over a decade ago, and it has stood within me ever since. The air was quiet in the way sealed places pretend to be finished.The disaster of 1934—266 miners killed—has been exhaustively archived:ventilation failures, ignored warnings, safety protocols treated as inconveniences, directors insulated from consequence. A litany of causes, carefully itemised, rehearsed as though catastrophe were a deviation rather than a condition. All necessary, perhaps, as exercises in accountability. And yet I left with a lingering dissatisfaction, a sense that something essential had been evacuated from the story. These explanations behaved like drains:channel the responsibility here, dam it there, and the ground might finally dry. As if better decisions could have redeemed a system whose logic depends on pressure, risk, expendability. As if extraction were not itself a method of catastrophe, producing death as reliably as it produces surplus.

Years later, someone climbed the old slag heap at nearby Bersham Colliery, where my grandfather (Andrew’s, that is) once descended into seams from which others did not return. Across the black spoil, they painted a phrase that refuses to settle: Cofiwch Dryweryn. Remember Tryweryn. Remember one of the very last Welsh monolingual villages submerged to supply water for Liverpool’s industrial expansion, a drowning recoded as a mirage of public good, an erasure sold as infrastructure. Capital accumulating through submersion. Another extraction, another promise that what is taken can be piped away without remainder, that distance dissolves obligation, that engineered absence can pass for resolution.

It felt like a recognition rather than an intervention. As though someone else had sensed that these were not separate histories but repetitions of the same operation, staged in different materials. Coal, water, labour, land. The mines closed. Entrances sealed. Concrete poured. The fantasy of closure preserved. Extraction’s afterlives, we are told, can be contained. And then the water returned. It always does. No matter how carefully flow is redirected, water remembers where the ground was persuaded—briefly—to behave otherwise. It seeps back through fractures, gathers in forgotten hollows, turns certainty into suspension. Dod yn ôlat fy nghoed.

What could we ask of capitalism today, in its rabid form of virulence, a malignant condition gripping the earth, and yet normalised into hiding? Where does it hide? What forms does it take when it claims to be finished with extraction? Where is its violence most aestheticised, and where is it most brutally naked? What does it ask us to celebrate, and what must we be trained not to see? Perhaps in sealed Welsh mines still bleeding acid decades after closure. Perhaps in Korail, beside Gulshan Lake in Dhaka, where wetness is framed as encroachment and life persists in the interstices of speculation, infrastructure, and neglect. Perhaps wherever water returns to places declared dry, insisting that nothing was ever resolved. It is this remainder beyond capture that enthrals us to think otherwise.

What if these sites—mines, reservoirs, drowned villages, informal settlements—are not exceptions but teachers? What if capitalism’s contemporary form is not visible in factories alone, but in its hydrological afterlives everywhere: in seepage, subsidence, slow poisoning, and return? Wetlandic thought begins here, not by adding another case to a catalogue of justices, but by refusing the fantasy that extraction ever ends. It asks us to read catastrophe not as an accident, but as sediment. To stay with the wetness long enough to feel how histories pool, how responsibility refuses to be drained, how the ground, patiently, remembers.

Capitalism dreams of draining and damming, but that dream would remain a fantasy without a siphon. It is the answer to capital's metaphysical stumbling block: how to take something without accepting what comes with it? As a riposte, capitalism offers the pipe (as both material artefact and extractive logic), its drama's mode of production's quintessential figure, its silver bullet offering fantasies of no leakage nor remainder. It wishes to convey without encounter, passing through the world without being altered by it. A good pipe does not leak. Leakage is failure, wetness is error. Or is it? We might call this the pipe dream: capitalism's perverse fetish for frictionless conveyance, an imaginary where capture takes place without remainder, where what is desired flows cleanly away and what is left behind simply disappears, out of sight and out of mind (Fanon has much to say about this). Here we see the twisted capitalist-colonial logic redux: coal sent through Cardiff docks to fuel the Empire's global projection of force, the extraction of exchange value from Welsh valleys supposedly disconnected from their insertion into imperial war machines, each infrastructural compass point(pit to canal to railway to dock to ship to coaling station) supposedly severing the connection, each pipe segment claiming innocence even as the entire apparatus depends on their seamless articulation. The pipe is how capitalism pretends it doesn't leave a wound, just an empty channel. But is this much less a void than an engineered absence? And a wound, left open, will eventually seep. The dream isn't dryness as such. The dream is discipline, is control: water moved, held, released, managed according to accumulation's (il)logic rather than the ground's own rhythm. This is what the pipe promises across its transformations, what persists beneath every technical innovation in extraction's long history.

The pipe was capitalism's liquid extraction, visible infrastructure where surplus accumulated at Cardiff's Coal Exchange striking global asset prices. Now extraction operates through numerous mechanisms. Micro-rents extracted through every digital interaction (how many do you pay, we ask!). Value evaporating from one site and reconcentrating as wealth in tax havens, server farms, investment portfolios. Harder to track?Certainly, yet the same forces prevailing with remarkable obduracy: siphoning off, making extractive geographies disappear from view while accumulated excess compounds elsewhere. Whether through the sharp-edged materiality of pipes or algorithmic flows, the fantasy that you can extract value cleanly persists, and the idea that distance severs connection remains, upholding mythic notions claiming the ground can and will not hold what was taken. But, surely, data doesn't float away into the ether. Server farms consume enormous quantities of water for cooling, draining cities and ecologies. “The Cloud” never lifts off from the ground, always stereotomic. Digital infrastructure demands physical transformation of landscapes, consumption of resources, displacement of peoples, production of toxic waste. Extraction’s structural violence may feel weightless to those who benefit from its mode of production, yet it remains stubbornly material for those swallowed up by capital’s voracious appetite, its seepages percolate through bodies all the same.

In the Welsh coalfields, maintaining the pipe-dream required violence so constant it became invisible. When shafts were sunk hundreds of meters into the earth, water had to be pumped continuously just to reach the coal seams. Dryness was manufactured, an ongoing triumph of engineering over geology. The labour of keeping the mine dry was as essential as extracting coal itself, yet it rarely appeared in any ledger, rendered foundational through its calculated erasure from accounting. Wetness became the enemy in this vision, the interfering presence that had to be expelled so the"real" work of extraction could proceed uncontested, on and on and on. When the mines finally closed through managed decline, a tapering of production, a choreographed withdrawal of capital from lands deemed surplus to requirements, the pumps eventually stopped. And when they did, wetness returned, but not innocently. It rose decidedly scarred, chemically transformed, carrying in solution what it had touched during its long absence. Benthygdros amser byr yw popeth a geir yn y byd hwn.

We are no geochemists. Our physical geography colleagues offer a neutral name for what lingers here: acid mine drainage. A technical phrase, heavy in the mouth, clinical in its cadence. Useful nonetheless, because it opens a fissure through which something else can be sensed. For centuries, coal and metals were pulled from the ground and named production. The act was dressed as teleology: progress unfolding as destiny, wealth conjured from depth, extraction framed as an inevitable companion to what we were told to call development.

And yet, abandonment does not end production. Even after the last shift, after the gates are sealed and capital migrates toward its next frontier, the mine continues to work. Only now it produces something else. Not coal, not metal, but a slow, corrosive poison—ochre water leaching through rock, acid carrying memory molecule by molecule. The ledger declares closure. The company dissolves into legal absence. Liability is shed through restructuring, through paperwork that behaves like evaporation. Profits reappear elsewhere, endlessly elsewhere, compounding far from their point of origin, far from the valley that bears the stain.

What remains is extraction’s real yield, its final and enduring commodity: contamination that refuses to end. An orange vein bleeding downhill. A stream emptied of life. A valley that carries dividends not just to shareholders but to the soil itself, paid in toxicity and time. The mine is not dead. It is still operational, still productive, showing no intention of stopping. Only the register has shifted. What once appeared as asset is now renamed liability; what was once wealth is now waste. And yet the boundary between these categories is thin, porous, unstable. It leaks.

Here, capitalism’s claim to boundedness collapses under its own residue. The fantasy that extraction can be temporally or spatially contained dissolves as the ground insists on continuity. The water remembers. It carries the chemistry of past decisions forward, refusing the comfort of closure. What seeps through the cracks is not an externality but a revelation: that the system never stopped working, that malignant profiteering and poison were always co-produced, and that the earth—patient, saturated—will not forget what it has been asked to hold.

This is not aftermath. It is the continuation.

Yes—this is where Korail folds back into Wales, but not as an opposite. Not outward versus inward as a neat binary (the wetland will punish us for binaries). More as two faces of the same drainage theology: one shows how extraction keeps producing poison after closure; the other shows how “development” produces poison during operation, by insisting the wet must become dry, the porous must become parcel, the lake must become a bordered amenity.

Korail sits beside Gulshan Lake, a water body cultivated as ornamental infrastructure for the wealthy: a scenic edge, a premium view, a promise of clean nature as lifestyle. And yet the lake is also a receiving body. It receives sewage and runoff from the affluent city’s own circuits while the settlement is made to carry the blame, as if proximity equals culpability. Here pollution is not simply what seeps out of a finished industry; it is what is routed through an ongoing apparatus—through pipes, through planning decisions, through enforcement that selects its targets. The system manufactures innocence by manufacturing direction: the waste must flow toward those who can be named as waste.

This is where “temporal inversion” matters.In Wales, the mine keeps working after the ledger has supposedly closed—acid and orange water continuing the production line by other means. In settlements like Korail, the ledger never closes: the city’s accumulation requires continuous acts of drainage, filling, edge-making, and disciplining. The violence is not only in what happens after extraction ceases, but in what happens when extraction is rebranded as improvement. Land is “created.” Wetness is treated as a defect. Water is framed as encroachment. The wetland is asked to behave like a plot.

City authorities and developers create dry ground by piping in sand despite ecological protections and designations, as though a legal boundary could do what geology will not. The act of filling becomes a ritual of certainty: pour soil, pour rubble, redraw the line, call it development. But the wetland refuses to stay filled. Every monsoon exposes the fiction. Not as punishment, but as physics, as memory, as the saturated ground reasserting its own capacities. Quite literally, compressed earth does not suddenly acquire drainage just because the plan requires it. You cannot extract land from a wetland without also extracting its ability to hold, filter, buffer, breathe. You can rename wetness as land on a map, but you cannot make water forget its routes.

So maybe the more accurate move is not“outward” versus “inward,” but afterlife versus pre-emptive afterlife. Wales shows the afterlife of extraction leaking outward once the profit has moved on. Korail shows the afterlife being manufactured in advance: pollution routed into the margins, wetness disciplined into nuisance, displacement kept ready as a policy instrument. Different techniques, same end: producing dryness sufficient for accumulation, producing separations—clean/dirty, formal/informal, lake/slum, nature/waste—that the ground itself will not maintain.

The lake, then, becomes a kind of witness. It receives what the city disavows. It holds together what planning insists must be kept apart. It tells us that “ornamental infrastructure” is never only ornament: it is governance by aesthetics, border-making by landscape, class power expressed through water’s edge. And Korail becomes a site where wetlandic thought is not metaphor but diagnosis: the insistence that porosity cannot be legislated away, that seepage is not failure but the real condition, and that every attempt to force dryness—through fill, through eviction, through blame—reveals, again and again, the impossibility of separating life from the wet grounds that make urban life possible.

We cannot drain our way into justice. The wetland refuses. And in that refusal is both the evidence of violence, and the opening for an otherwise.

The apparatus is technical and epistemic at once, acting on matter and meaning together. Pumps and sluices, yes—but also ledgers that decide what counts as cost, cadastral maps that make land legible to capital, deeds that turn use into ownership. The ditch and the spreadsheet co-produce one another. What varies across these sites is tempo and technique—the speed of enclosure, the intensity of violence, the timing of contamination. What persists is the belief that distance breaks responsibility, that extraction can be finished with, that the ground, once altered, will remain silent. It does not.

All of this requires a different mode of thought. So we ask you to think with wetness—as method, as epistemology, as refusal, as attention to what persists beneath every administrative attempt at separation. Anthropologist Luisa Cortesi poses a deceptively simple question: what do we call land that official maps say is not floodplain, yet floods anyway—ground that sinks because rivers still run beneath it, invisible to surveying?“Wetland” does not quite work; it is too discrete, too technical. The insurance map says one thing, the ground does another, and people are left without language for their experience. Cortesi offers waterland as a vernacular name for what water and land actually do together. Neither can be understood in isolation. What appears as dichotomy—wet and dry, solid and fluid—is ontologically inseparable.

Wetlandic thought begins here, in refusing the separation that extraction requires and administration enforces. But this is not a romantic celebration of flow, nor another tired claim that everything is connected. It asks instead: what language do we need for a world of seepage that does not stop, of returns that cannot be prevented, of ground doing what maps insist it should not? This demands different concepts: viscosity rather than flow, saturation rather than circulation, remainder rather than relation. What accumulates is not connection, but what refuses removal.

Simondon helps here (Chabot 2013). He described individuation not as a completed state but as an unfinished process: beings emerge from a charged milieu yet never fully detach from it. The sovereign individual imagined by capitalism—self-contained, accumulative, frictionless—depends on the nation-state, which depends on capitalism, which depends on the pipe. None exists alone. Individuation never finishes. The ground from which something emerges retains the capacity to reassert itself. Extraction rests on a false ontology: it treats things as already separate, already done. Coal is imagined as detachable from mountain; land as isolable from wetness; value as liftable from time and process. What later appears as damage or externality—flooding, contamination, displacement—is the preindividual milieu returning, distorted, because the world refuses the fiction of clean separation.

Capitalism has always been haunted. Arundhati Roy calls contemporary capitalism a ghost story: wealth without bodies, violence without authors. Historian Tithi Bhattacharya (2024) shows how colonial rule reorganised haunting itself. Older worlds allowed the living and nonliving to coexist; colonial governance demanded separation. Death was relocated, sanitised, administered through statistics, sanitation, epidemiology. Clean divisions—life and death, inside and outside, productive and waste space—became conditions of rule.

Some argue that we have moved on from capitalism to another stage, an external movement into technofeudalism, platform monopoly, rentier extraction… The distinction may matter politically in privileged circles. Yet from the perspective of ground that still bleeds, or wetlands that refuse to stay filled, the malignancy of capitalism, its core logic of extraction, accumulation and delusion, looks remarkably consistent and present. Whatever we call it, the same grammar persists: extract value from particular sites and bodies, siphon it elsewhere through techno-managerial systems, accumulate it at a distance, delude the desire and leave the remainder to absorb the consequences. I’r pant y rhed y dŵr.

A note here: Drainage alone cannot make a system endure, nor can accumulation explain why its violences are so often tolerated, even desired.Something else is at work—an optics, a shimmer, an infrastructure of delusion, a meta-operative logic that sustains, promotes, virulates the malignancy in capitalism—the ability to make others desire the drainage and the dam as the value in itself. The drained ground is rarely presented as loss; it is reframed as improvement, order, beauty, progress. The reservoir becomes a vista. The sealed mine becomes heritage. The filled wetland becomes “land.” This is not concealment so much as enchantment: a way of making extraction look like care, and accumulation feel like common sense. Remember that Deleuze asked us to go against common sense, to see through the shimmering veil.

What resists the delusion—what crawls under the skin—is the ground remembering, the remainder of all the calculation. Lungs holding coal dust decades after closure. Wetlands rising despite fill and compaction. Mines bleeding acid into dead streams. To think wetlandically is to refuse clean narratives and resolved arguments, to stay with the seepage (staying with the trouble isn’t enough, really)—to remain in the uncomfortable space where memory, anger, analysis, and implication bleed into one another.

There is always the temptation of tidy frameworks: core and periphery, colony and metropole, Global North and South. These do important work. But they also smooth friction, make comparison too pipe-like. What matters instead is attention to how extraction operates differently across sites while drawing on the same sets of desire: control over water, land dry enough for ownership, value without remainder, separation without violence. Wetlandic thought attends to what persists, to what returns, to what refuses resolution.

Between coal mines in Wales and Korail in Bangladesh, between sealed mine and flooded settlement, between ground that bleeds and ground that will not stay filled, we offer “intensions”, not closure. Only an insistence: once something is taken, the ground does not return to how it was. The mountain bleeds. The wetland floods. Something continues to seep, despite every attempt to pipe it away. It says:

Er gwaetha pawb a phopeth, ry’n ni yma o hyd.

(Despite everything, we are still here.)

References/Readings:

Bhattacharya, T. (2024). Ghostly past,capitalist presence: a social history of fear in colonial Bengal. DukeUniversity Press.

Chabot, P. (2013). The philosophy ofSimondon: Between technology and individuation. A&C Black.

Cortesi, L. (2022). Hydrotopias andwaterland. Geoforum, 131, 215-222.

Roy, A. (2015). Capitalism: A Ghost Story.London: Verso Books.

How to cite this article: Hughes, Andrew, and Shafique, Tanzil (2026). "Capitalism as Drainage, Dams and Delusions (A Thousand Wet-Lands)," Interrogations, doi: 10.5281/zenodo.18303744

----

Read the first installment: Rivulet 1 / Let us be wet…

Read the second installment: Wetness against the three gods